Tadcaster-based author Tony Morgan has uncovered some fascinating facts about York in Tudor times for his new book

We hear a lot about the Romans and Vikings but less about what happened in Tudor York.

As I’ve carried out research, written books and give history talks on this fascinating period in the city’s history, I think it’s time to put this right.

I’d like to share a few surprising facts and findings from my research. I’d love to hear how many of them you knew about already and which ones may have surprised you.

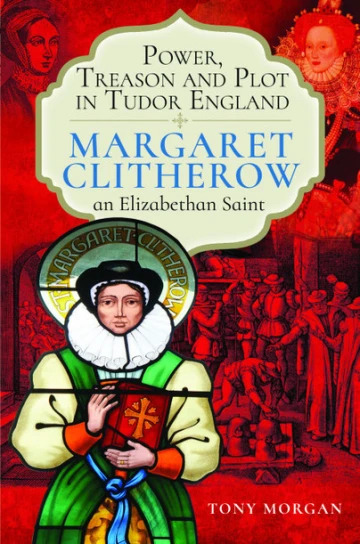

Power, Treason and Plot in Tudor England by Tony Morgan

Non-fiction history book exploring the power struggles of Tudor England, their impact on the city of York and the life and death of York woman Margaret Clitherow. The book has featured quite highly in Amazon’s history charts.

Buy: Pen and Sword Books / Amazon

1. When Henry VII came to York, he drank the city dry

The first Tudor king, Henry VII, visited York twice – shortly after he came to the throne in 1486 and again in 1487.

On the second occasion, Henry and his men had recently put down a rebellion and were in a mood to celebrate.

It’s reported the city was “dronkyn drye”. Once he’d sobered up, the King knighted York’s mayor William Todd and the alderman Richard York for their loyalty to the crown.

2. York supported a major rebellion against Henry VIII

A rebellion called the Pilgrimage of Grace began in Beverley in 1536 against Henry VIII’s religious and other policy changes.

When the rebels came to York, the city leaders opened the gates and welcomed them in. Despite being promised their demands would be met, many of the rebels were later arrested and executed.

Their leader, Robert Aske, was hanged in chains at Clifford’s Tower. His body was left in plain sight to deter future potential rebels.

3. The closure of York’s religious houses caused a recession

With the rebels defeated, Henry VIII and his adviser Thomas Cromwell pushed forward with the dissolution of the monasteries to raise money for the crown.

Between 1538 and 1539, York saw the closure of St Andrew’s and Holy Trinity priories, four friaries, St Leonard’s Hospital and St Mary’s (or York) Abbey.

Numerous friars, nuns, monks and canons were turfed onto the street. With income from the religious houses lost, York suffered a major recession.

4. York’s leaders apologised to Henry VIII at Fulford Cross

In 1541, King Henry VIII arrived at Fulford Cross with his fifth wife Catherine Howard and an army of around 5,000 men. Henry wanted to show the city (and the north in general) what might happen if they didn’t pledge allegiance to the crown.

The city’s mayor, Robert Hall, York’s aldermen and other dignitaries sank to their knees before the king and apologised “from the bottoms of their stomachs” for past misdemeanours.

The King and Queen were each given a silver cup filled with gold from the city’s coffers. Henry remained in York, at the King’s Manor, for eleven long days before eventually leaving, as York’s citizens let out a collective sigh of relief.

[adrotate group=”3″]

5. After Henry VIII’s visit, no Tudor monarch ever came to York again

Henry VIII was succeeded by his son, Edward VI. When Edward died, his half-sister was eventually crowned Queen Mary I.

Mary in turn was succeeded by their half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I. These were the last Tudor monarchs and none of them visited York.

As Elizabeth reigned for 45 years, perhaps this was quite surprising, although the monarch’s travel plans were complex and expensive and, of course, the roads weren’t very good in those days.

However, the next king, James Stuart, visited York in 1603. He called into the city on his way down south from Edinburgh to London, where he was crowned James I.

Two years later, York’s Guy Fawkes tried to blow him up in Parliament.

6. In Tudor times, the Lord Mayor set prices in the city’s markets

One of the Lord Mayor’s responsibilities in Tudor York was to act as clerk of the markets. This gave the mayor the ability to set the prices of goods sold.

In 1555, Lord Mayor William Beckwith “went through the market to see reasonable price of vitals”. When he encountered a butcher “sellying his fleissh excessively”, the man was instructed to reduce his prices, in order to ensure they were more “reasonable for the poor”.

I wonder if City of York Council might try the same thing these days.

7. Ouse Bridge was partially destroyed by a storm in 1564

Ouse Bridge was the only crossing over the river Ouse in Tudor York. In 1564, the bridge was seriously damaged, as a deluge of water swept down the river following a heavy snowfall and sudden thaw.

Two bows of one arch and twelve houses were washed away. At least a dozen people drowned.

The Corporation of York, aided by donations from wealthy merchants, paid for repairs to the bridge. These were completed two years later, and the river was dredged.

Following this, the riverbank was built up to protect the city from future deluges. Of course, we know this wasn’t fully successful, as the city continues to be impacted by flooding today.

8. Money lending was rife, and the Archbishop wasn’t happy

With York’s combination of wealth and poverty, money lending was rife in the city. Lenders often charged borrowers much higher rates of interest than the ten per cent defined by law.

During his inaugural sermon in 1577, the new Archbishop of York Edwin Sandys raged against this practice and decried the money lenders for charging immoral rates of interest. In 1585, the archbishop took action against many of those involved, including some of York’s leading citizens.

Forty men were forced to forfeit much of the interest they’d earned. The archbishop subsequently tried to forbid the charging of any interest at all, even at the legal rate, but this was blocked by other officials.

9. Knavesmire was more famous for executions than horse racing

Each town and city had a favoured location for the gallows. In York, this was the Knavesmire. Men and women were executed, some hanged, and others hanged, drawn and quartered, a particularly horrible death.

Here are some examples.

- In 1576, Edward de Satre and Sarah Houslay were hanged for passing off forged promissory notes.

- In 1582, George Foster of Tadcaster was executed for coining (counterfeiting).

- In 1592, Anthony Hodson was executed for housebreaking and robbery.

People were sometimes executed for “religious crimes”. In 1585, Marmaduke Bowes was said to have been executed after being found guilty of simply giving a Catholic priest a drink.

[tptn_list limit=3 daily=1 hour_range=1]

10. There wasn’t a major outbreak of disease in York during the reign of Elizabeth I

Before Elizabeth’s coronation, York was regularly impacted by epidemics and diseases. There were outbreaks of bubonic plague in Henry’s VIII’s time, followed by plague and sweating sickness under Edward VI.

Records show particularly heavy rates of mortality in 1550 and 1551. The parish of St Martin’s, Micklegate, is thought to have lost half its population.

The final year of Mary’s reign saw the “new ague”, a virulent strain of influenza. Death rates in York were once again high.

After this, there was no major outbreak of disease in the city until during the first year of James I’s reign, when the plague returned. Perhaps, Elizabeth should have visited after all.

11. Guy Fawkes wasn’t the only Gunpowder Plotter to go to St Peter’s School

Here is a very famous picture of the Gunpowder Plotters. These were the men who tried to blow up Parliament and kill King James I on 5 November, 1605.

Three of the eight men attended St Peter’s School in York, although it wasn’t located in Bootham at that time. The brothers Christopher and John Wright from the East Riding were amongst Guy Fawkes’ schoolmates.

Spoiler alert! In my novel The Pearl of York, Treason and Plot Guy Fawkes gets expelled for getting into a fight!

12. Margaret Clitherow was executed for refusing to make a plea

This is a particularly sad and well-known episode in York’s history. On 25 March, 1586, butcher’s wife Margaret Clitherow was pressed to death for refusing to plead guilty or not guilty to harbouring Catholic priests in her house.

Margaret’s story is remarkable. Her arrest was the culmination of national issues, local politics and family intrigue.

A week before Margaret was arrested, her stepfather Henry Maye was made Lord Mayor of York. I explore her story in The Pearl of York, Treason and Plot and in my new non-fiction book Power, Treason and Plot in Tudor England.

She was a brave and remarkable woman, who we should really call Saint Margaret Clitherow, as she was made a saint in 1970. You can visit a shrine to Saint Margaret in the Shambles and/or see a relic said to be her hand in the Bar Convent on Blossom Street.