What was York like at the outbreak of World War One, and how did the city react? Chris Titley looks back

1. The outbreak of the First World War was announced to the citizens of York outside the offices of the Yorkshire Herald Building, where there were “loud and prolonged cheers… and the National Anthem was heartily sung”.

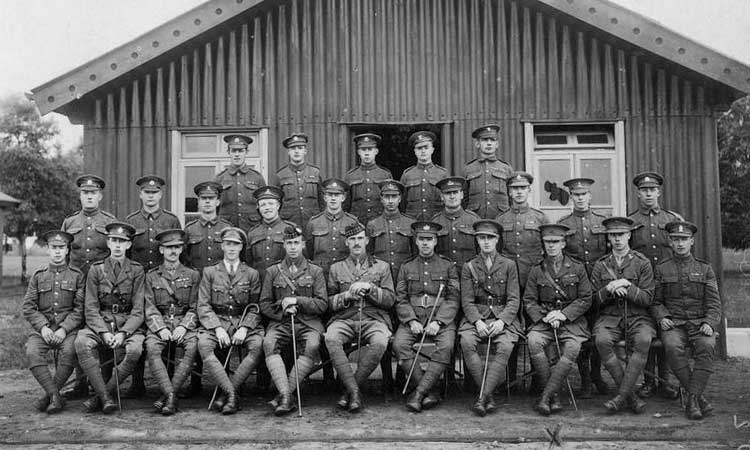

2. York was a garrison town. When war was declared on Germany on August 4, 1914, the 1st East Yorkshire Regiment, the Scots Greys and the 3rd and 4th West Yorkshires were stationed at either the cavalry or infantry barracks in Fulford. Pilots from the Royal Flying Corps – the air arm of the British Army – were awaiting orders on Knavesmire.

3. Strensall barracks, by contrast, was deserted. The King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and the Notts and Derby regiment had left for Pontefract, Sheffield and Derby.

4. Panic buying is nothing new. A few days before the official outbreak of hostilities, York shoppers chose to stock up in readiness: Nessgate grocers Banks and Company reported that they had sold dozens of sides of bacon and around 400 hams at a time they would normally have expected to sell 30 or 40.

5. Bad teeth could prevent you from joining the army. George Coverdale, the chemists on Parliament Street, did dentistry. In an advert in the Yorkshire Evening Press Coverdales offered to whip out your rotten teeth for a bargain price so you could join up.

6. Live entertainment in the early weeks of war included The Story Of The Rosary followed by Charley’s Aunt at the Theatre Royal. Meanwhile the Empire (now the Grand Opera House) had its usual variety shows, with Fred Keeton and Alfredo topping the bill.

7. York cinemas were doing good business. The Electric Theatre on Fossgate was the city’s first purpose-built cinema when it opened in 1911. At the outbreak of war the Victoria Hall on Goodramgate was showing The Master Crook Turns Detective (“A detective story which holds the interest throughout”). A former roller skating rink, the City Picture Palace was screening The White Lie, a film in three parts by William le Queux.

8. At the Hippodrome on New Street – formerly the New Picture Palace when it became York’s first permanent cinema in 1908 – all the pictures were “accompanied by the Hippodrome Orchestra”. This wasn’t enough to save it, however, and later in 1914 it closed, and it was used for a while as a hostel for World War One troops.

9. The first war picture to be shown in York was The Looters of Liege, shown at the Victoria Hall in the third week of August. Screened at the same time were locally made films of the departure of the Scots Greys from the city and some of the Seaforths and Warwickshires going through or from York.

10. The commandeering of horses for the war effort caused consternation. On August 7, 1914, the Press reported how the military authorities had stopped farm wagons in Blossom Street, taken the horses for a small payment, and left the farmers stuck with their carts and nothing to pull them.

11. Military authorities commandeered the Barbican Road cattle market – where the Barbican Centre now stands – as a depot for the requisitioned horses.

12. Lord Kitchener’s famous poster “Your King and Country Needs You”, asking for volunteers between 19 and 30 years of age, appeared in the columns of the York papers on August 8.

13. York Art Gallery – part of what was then known as Exhibition Buildings – was the city’s recruitment centre. It was also used for postal services, as well as a YMCA for the troops.

14. York did not have the best record for recruitment. Towards the end of August 1914 there was an average enlistment of 34 men a day joining Kitchener’s army. “These are excellent figures,” said a report in the Press, “but the city of York can take little credit for them, as more than 93 per cent of the enlistments emanate from outside the boundaries. York itself is reputed to be one of the most difficult in England for obtaining recruits.”

15. Some local employers did their bit to aid recruitment. The York Corporation, The Rowntree’s Factory and Leetham’s Flour Mill on Walmgate were among the first to promise to pay an enlisted man’s wage to his wife to ensure the upkeep of the families left behind.

16. The most acclaimed recruiting story was that of the ten Calpin brothers who left the family home on Walmgate and enlisted in 1914. Lord Mayor Henry Rhodes Brown wrote to their parents stating that “it will be hard for anyone in the Empire to equal your fine record of ten sons all serving their country”. All survived the war and returned home, although one, Joseph, died a few weeks later from the ongoing effects of gas poisoning.

17. News of the first York war wounded soon arrived. The Scots Greys, so recently stationed in the city, had been badly cut up during the retreat from Le Mons.

18. The first local men to die in the First World War as listed by the Press included:

18. The first local men to die in the First World War as listed by the Press included:

- Stoker Petty Officer George F Banks, born in Lord Mayor’s Walk and educated at Queen Street School

- Sgt Orderly Room Clerk Alexander Hutchison of the 1st Cameron Highlanders, educated at Fishergate and killed on the Aisne on September 25

- Corporal W Newton of the 6th Dragoon Guards (Carabineers), killed on September 24

- Private Walter Rickard, an ex-Rowntree employee who joined the Scots Guards in 1913, killed on the first day of the Battle of the Aisne

- Major Swetenham, well known in York as one of the Scots Greys: his death reported early in September

19. York was soon overflowing with troops. By the end of September 2014, there were 3,500 members of the West Yorkshire Regiment here, 2,400 of them in the cavalry barracks. The 5th Cavalry Reserve was on the Knavesmire, where the racecourse grandstand was equipped with 1,500 beds. Between 6,000 and 7,000 were stationed at Strensall by the end of October.

20. Fears that soldiers would spend too much time drinking led the York licensing bench to restrict alcohol sales. All pubs, clubs and restaurants were forced to close at 9pm each night. This led one York licensee to comment that “if the present government had fought the Germans in the same way as they had fought the publicans, the Germans would have been beaten by now”.

21. The military post office in the Central Hall of Exhibition Buildings sent thousands of letters and parcels to the front in France and Belgium, and further afield to every corner of the Empire.

22. Many Belgian refugees who came to York were housed at New Earswick, Rowntree’s model village. Nine houses were donated rent-free by the directors. Rowntree’s workers helped furnish and decorate these homes for the refugees and also paid a weekly donation of 1d to support the Belgian families.

23. At this time the railway was York’s biggest employer. Some 5,000 men of the North Eastern Railway signed up to fight – a tenth of the total workforce. Women took over a lot of these jobs, initially as clerks and ticket inspectors, but in 1917 the NER inaugurated its first team of policewomen.

24. Women took many other jobs formerly reserved for men – including driving trams.

25. Children played their part in the war effort. They were encouraged to collect conkers and were paid a reward of seven shillings and sixpence for every hundredweight they sent to the War Office. The conkers went to chemical factories to make acetone, a component of the cordite propellant used for shells and bullets.

26. Many schools were given new roles after the outbreak of hostilities. For a time Scarcroft Road School was turned into a post office. Haxby Road School was given over to the military after lessons had finished for the day.

27. The Castle Prison held so many “enemy aliens” during the first year of the war that a tented encampment was created on the Eye Of York. German-born civilians from across the country were imprisoned in York.

28. On August 5, 1914, the Aliens Restriction Act came into force to crack down on spying. It prevented Germans resident in Britain from travelling more than five miles from their homes. An early victim of the act was 25 year-old chef called Karl Lorentz, who had lived in York for nine years. He was prosecuted for taking a trip to Harrogate, unaware that he now needed a permit to do so.

29. Later a concentration camp was built on the site of the old North-Eastern Engineering Works on Leeman Road to cope with the ever-increasing numbers of interred “aliens”. The camp could hold 1,700 prisoners. Surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, it also had a hospital, shop and hairdressers. Crowds would assemble on Sundays to stare at the prisoners, even throwing food and gifts over the fence.

30. It also held German prisoners of war. Three hundred were transferred to Leeman Road from Scotland in September 1914. Thousands of people watched them arrive. The Germans sang national airs, accompanied by civilian prisoners on accordions.

31. Extra hospitals also sprang up to cope with an influx of men injured on the front. One was on the site of the Quaker Meeting House off Clifford Street. Another was where York St John University is today, off Lord Mayor’s Walk.

32. Many aspects of York life were turned upside down by the outbreak of the Great War. But the prevailing feeling was this would be a short lived sacrifice and the war would soon be over. It was an optimism which we now all know was sadly misplaced.